Since last summer, I’ve been trying to trace the ordeal suffered by the family of Rosa Josefowicz, my mother’s adopted cousin.

So, on August 31, 2022, I went to Saint-Martin-Vésubie in search of the plaque erected “in memory of the Jews under house arrest in Saint-Martin-Vésubie, fleeing Nazi barbarism across the mountains, arrested at Borgo San Dalmazzo, then deported to Auschwitz”. I was hoping to find the name of Rosa’s family, who I had understood were among those who made the crossing of the Alps in September 1943. A few days later, I discover that a “Marche de la Mémoire” (Memory Walk) is being organized in their honor.

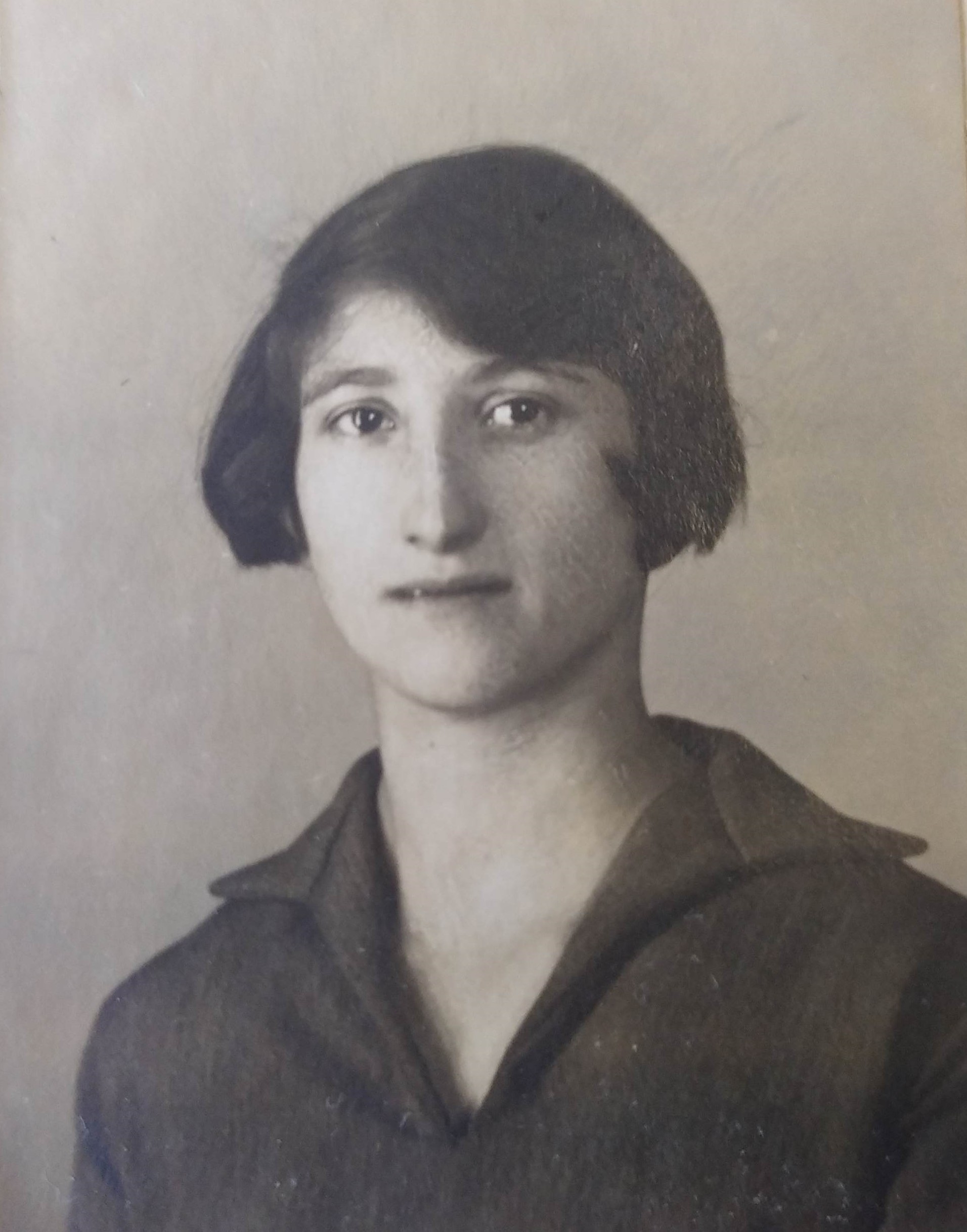

In fact, I was doing some research to find out more about her history. Orphaned and adopted, she has no memory of her family, and knows nothing of their tragedy except that they disappeared at Auschwitz.

Her parents, Zelig and Estera, Bella, their baby who was less than two years old, Zelig’s parents, Szmul and Chaja, aged 67, a first cousin, Szyfra née Jozefowicz, her husband Ernst Kramm and their tiny baby Charles, born in July in Digne; all left on convoy 64 from Drancy for Auschwitz, where they died.

It was the Drancy files that put me on the trail of their journey; in addition to a sum in francs, they had also deposited a few lire, and their registered address was Borgo. A quick search put me on the trail of the Saint-Martin Jews who had crossed the Alps in September 1943, over 300 of whom had been imprisoned in a former barracks at Borgo San Dalmazzo in the Italian Piedmont, on the other side of the Alps, where they remained for two months before being transported to Drancy. Other Drancy files offer new information: their home was Venanson, a tiny village above Saint-Martin-Vésubie.

But only Szyfra, Ernst and Charles Kramm appear on the monument in the village; neither her parents, whom she doesn’t remember, nor her little sister, whom she never knew, nor her grandparents, whom she could not envisage had existed, are listed; probably because they did not stay in Saint-Martin, but in Venanson.

But whether in Saint-Martin for the Szyfra family or in Venanson, their stay was very brief, barely a few days.

They all came from the Basses-Alpes region, where they had been under assigned residence for several months in 1943, under the protection and surveillance of the Italian occupying army: the Josefowiczes in Moustiers-Sainte-Marie, the Kramms in Castellane: during this stay, little Charles was born.

They were in fact protected, as they were all wanted by the French authorities, the men, incorporated into foreign labor groups for having fled when they were not allowed to leave the place where they were officially billeted, and the roundup of the southern zone on August 26, 1942 was in preparation. The family was obliged to reside in Capestang in the Hérault. It was here that Szyfra married Ernst, originally from Bukovina, and incorporated into a group of foreign workers. At the end of 1942, following the German occupation of the southern zone, the grandparents, the women and the baby born in December 1941 in Béziers, were no longer allowed to reside in the coastal zone, all the more so as “active searches” put them in danger and another round-up was looming in February 1943.

It’s easy to imagine that the two families decided to disappear; they made their way to the Italian zone, first via Nice, where the rue Dubouchage committee had to send them to the mountains, Moustiers-Sainte-Marie and Castellane. At the very beginning of September 1943, when Italy was preparing to end the war, and the Germans were to replace the Italians, they were rushed to Saint-Martin-Vésubie.

The trek across the Alps was almost the end of their journey: they had left Poland in the very early thirties, for Antwerp, where their existence was fairly peaceful; the family group of six siblings, lived close to each other, almost all working as tailors. Rosa was born there.

Then came the war and the exodus; Zelig chose, under what circumstances I don’t yet know, to leave for France, while almost all his brothers and sisters remained in Belgium, where they all suffered the Shoah: none of them ever returned. One brother lived in France and was detained in the Green Ticket Roundup in 1941. The Josefowicz siblings disappeared entirely.

The survivors were few in number: Rosa, who survived thanks to her parents, who entrusted her to the care of the OSE at the Château de Chabannes in the summer of 1941; her French cousin, Jacques, who hid near Grenoble with his mother; a cousin, Rachel, a child hidden in Belgium, and two older cousins, one of whom returned from Auschwitz.

Rosa has only known this story, her story, since April; 88-year-old Rosa and 85-year-old Jacques, the only first cousins still alive, met a few weeks ago.

His and Jacques’ families have also met: almost all of them live in Paris, and in the 12th arrondissement!

Claudine Hérody-Pierre

Claudine Hérody-Pierre is a retired history teacher and historian.

Félicitations pour cette enquête fouillée.